Translation of South African poetry

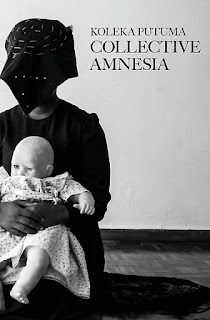

A few weeks ago I wrote a review of Koleka Putumas book “Collective Amnesia”. It was translated into Danish last year and published by the small press “Rebel With A Cause”. While I was reading the Danish version of the book I felt a disturbance. I wanted to go to the source – to read the original. But does the original exist? Isn’t everything just a copy of something else? It made me think about definitions of translation. For me a translation ought to be perceived as an independent piece of art. The transcript of text from one language to another is not a simple and innocent process. I reject the notion that a translated poem mirrors the original written poem, because a poem can only be written in another language through a transformation. But a successful translated poem has to be true to the intention of the poet and loyal to the language of the poem.

What does

this really mean?

A translated poem must capture a similar bodily, psychological and linguistic sensation from the poem written by the author. It means that the poem in itself on paper and graphic structure might be very different, because it is another language and cultural setting.

In my review I do not write anything about the quality of the translation, because I have no formal reason to challenge the translator and her translation, but already by reading the cover text and the press release I had a peculiar feeling – a similar feeling followed me while reading the collection of poems on the pages in the book, although I have no specific examples to explain my shaky and abrupt reading.

The poems deal with problems of race, sexuality and gender. These issues are in South Africa connected to traumas, violence, despair and fear– in a country where apartheid and colonialism is still a day to day experience for everyone. It can be very difficult to comprehend if you have grown up in the shadow of the Danish Welfare State.

A translated poem must capture a similar bodily, psychological and linguistic sensation from the poem written by the author. It means that the poem in itself on paper and graphic structure might be very different, because it is another language and cultural setting.

In my review I do not write anything about the quality of the translation, because I have no formal reason to challenge the translator and her translation, but already by reading the cover text and the press release I had a peculiar feeling – a similar feeling followed me while reading the collection of poems on the pages in the book, although I have no specific examples to explain my shaky and abrupt reading.

The poems deal with problems of race, sexuality and gender. These issues are in South Africa connected to traumas, violence, despair and fear– in a country where apartheid and colonialism is still a day to day experience for everyone. It can be very difficult to comprehend if you have grown up in the shadow of the Danish Welfare State.

How does

this play a role for the translation of a collection of poetry?

You are

probably already very angry because I do not let you read Koleka Putuma’s poems

in peace, but you will not be able to read her poetry without circumstance and

context; especially because her poetry draws so very directly from a black,

queer woman’s experiences in Cape Town, South Africa. In order to really read

her you must try to find something in yourself that can make you feel a light –

no matter how weak – version of the pain behind the poems. This does not mean you need to have felt

apartheid on your body or be black or queer to read and understand the poems.

But I will

encourage anyone to find a place in their mental mind or a tab of experience

that resemble what take place in the poetry – no matter how slight, soft and

gentle – then exaggerate, multiply and explode the sensation. In this state of

mind you shall begin reading – not before. The same should underlie every

motion of a translator’s work.

Koleka

Putuma’s poetry comes from a place we could call identity politics. In a Danish

context identity politics has a complicated reputation – to name something

identity politics is in the Danish public debate often regarded as a degrading

it in importance, because it is perceived as an opinion based on a particular

interest without acknowledging a broader picture. In reading Koleka Putuma it

is important to recognize that identity politics in South Africa indeed is

connected to a broader agenda – race and gender is the broader picture. Race is

such an important category than even as a foreigner or visitor you would very

quickly find it impossible to phrase a single sentence without the implication

of race and color. Therefor reading Koleka Putuma out of context would be devastating.

In my

review of Putumas poems I mention a documentary (Listen/Luister), which I

recommend as a brief introduction to being black in a predominately white

neighborhood in South African – not during apartheid, but today.

The reviewwritten in Danish was published by Globalnyt one month ago.

Comments